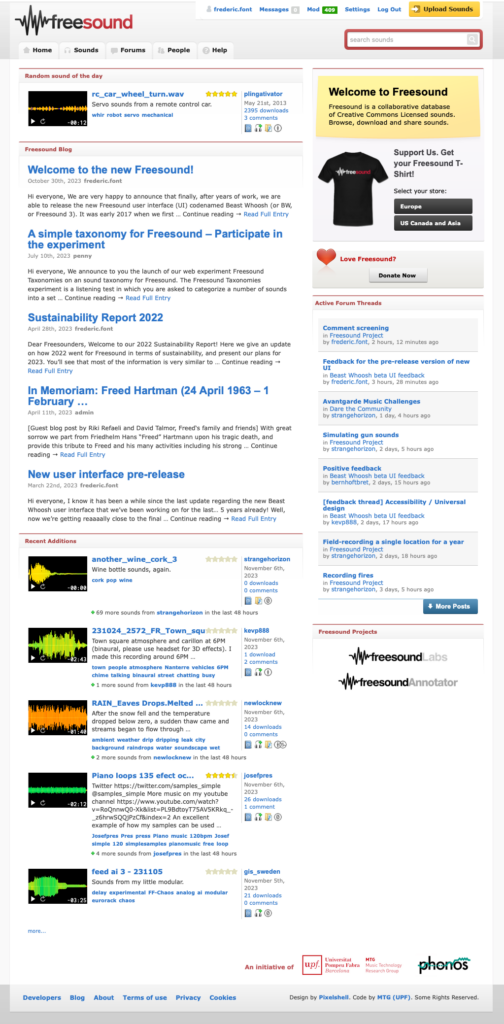

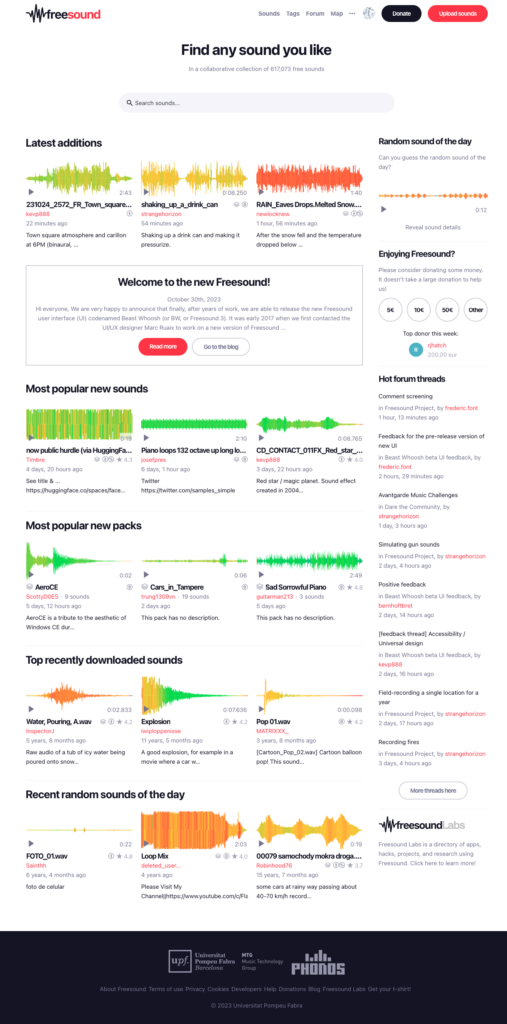

In recent years, the phrase Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become part of our everyday conversations. In particular, since the explosion of generative AI models like ChatGPT or other models that can generate high-quality audio (e.g. AudioGen, AudioLDM 2, and Stable Audio Open, which has just been released and is trained with Freesound sounds), AI systems have demonstrated being capable of doing things which were unimaginable only some years ago. We don’t know how AI will impact society at large, but it is very clear that AI is here to stay and that it will more and more become an important element in our lives. This is raising concerns, for example, within the artistic community, AI can be seen as a potential threat to the way in which many artists make their living, and one that questions the values of effort, skill and creativity. Concerns about the potential impact of AI on a platform like Freesound have also been expressed in the Freesound forums. Here, at the Music Technology Group of Universitat Pompeu Fabra where Freesound happens, we have also been discussing such concerns. For those who don’t know, the Freesound platform was started (and is still developed and maintained) in the context of a research group at a public university, and the open nature of the platform makes it ideal as a resource for audio research, not only for our university but for hundreds of other universities, research centres, companies and individuals all over the world. The relationship between Freesound and AI has therefore been existing since the beginning of Freesound, but only recently, with generative AI, AI has become an object of extensive public debate. For all these reasons, we have decided to write a blog post to state our position in the era of generative AI, to discuss how we think Freesound stands in relation to AI threats and opportunities, and how we expect Freesound to become a good example of AI being used as a tool to benefit the community. So, with no further ado, let’s get started!

The threats of AI

We would most likely all agree that the idea of AI as a threat to a community like Freesound manifests because of the developments in generative AI, which bear the idea that recording and uploading sounds might become redundant because we’ll be able to generate all the sounds that we want by feeding prompts to an AI model. The way we see it, such models pose two specific threats which could be referred to as AI sound flooding, and the replacement of Freesound by AI. Let’s discuss them separately and see which actions could be taken to mitigate potential issues derived from these threats.

AI sound flooding

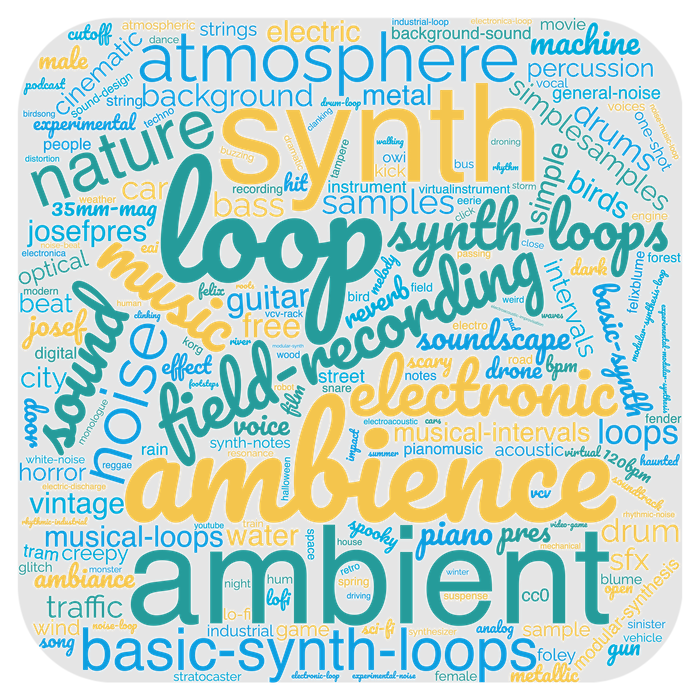

If AI gives us the capability to quickly generate thousands of unique sounds using generative models, it could happen that huge amounts of AI-generated content get uploaded to Freesound, diluting human-crafted sounds and reducing the overall quality of search results. Even assuming generative sound AI systems reach a quality which is comparable to human-crafted sounds, some of these sounds will be fake. For example, think of an automatically generated “crowd ambience in the streets of Barcelona”, we would not want users to believe these are actual real recordings from Barcelona, even though the sounds could be of good quality and reusable. Also, sounds generated with AI might be accompanied by AI-generated descriptions which could be inaccurate or lack relevant contextual information that only real authors could provide. Finally, AI-generated sounds will most likely present a much higher level of homogeneity than original sounds because these are severely restricted by the capabilities of the generative models that produced them. Altogether, an AI sound flooding would lower the value and quality of Freesound, and that would have an obvious negative impact on the community.

A way to address such potential problems is to make sure that the AI-generated content which gets uploaded to Freesound also gets flagged as such. Having content flagged would allow us to implement filters and highlight, if need be, the AI nature of sounds. Flagging could be achieved by adding an option to mark sounds as being “AI generated” in the sound description form, but also by using systems that will automatically identify content which was generated with AI (e.g. using watermarks or other methods which will be, ironically, AI-powered). In fact, the idea of being able to identify AI-generated content is a core concept of the recently approved EU AI Act, and a very relevant research topic in itself.

That said, let us mention that we don’t see the flooding problem as a very likely scenario, at least in quantities that would severely impact Freesound. We believe that, unlike other platforms in which users upload content and get economic rewards for its consumption, Freesound users have no incentives for uploading large amounts of content and abusing our terms. Furthermore, the relatively small size of Freesound plays in our favour: in case of need, we might be able to impose more strict rules for uploading sounds and manual checks which would allow us to avoid content flooding.

Replacement of Freesound by AI

The other big threat of generative AI in relation to Freesound is the potential of AI to become a replacement for Freesound in the sense that people looking for sounds might not need to visit Freesound if their AI assistant directly creates the sounds they need and these sounds are of good enough quality. This might result in less overall activity on the website (less traffic, fewer downloads, fewer ratings, fewer comments, etc), and possibly fewer sounds being uploaded and fewer user donations, which would affect the richness of the Freesound community.

Nevertheless, we will all agree that generative AI models can only emulate a small bit of the experience of searching and sharing sounds within a user community. Freesound is much more than just a collection of audio files, and all the social activity and personal stories are something that would not be replaced by an AI generative model. It is difficult to estimate what the impact of a really good generative model could have in terms of Freesound website activity, yet it is plausible to believe that a significant chunk of the Freesound users who only download sounds and are not interested in the community aspects of Freesound, might not feel the need to use Freesound again. But it is also true that Freesound would remain a unique sound-sharing website for thousands of users around the world, and its added value when compared to AI-generated solutions would still be enormous.

We believe that to address the threat of AI replacing Freesound, we have to put special emphasis on the community aspects, for example, implementing new features that promote activity within the community. We also have to continue carrying out research activities that allow us to deploy state-of-the-art tools for searching and discovering sounds within Freesound. By maintaining such a competitive advantage over the experience of generating sounds with AI, we don’t think AI will become a real threat to Freesound’s sustainability.

Can my sounds be used to train AI models?

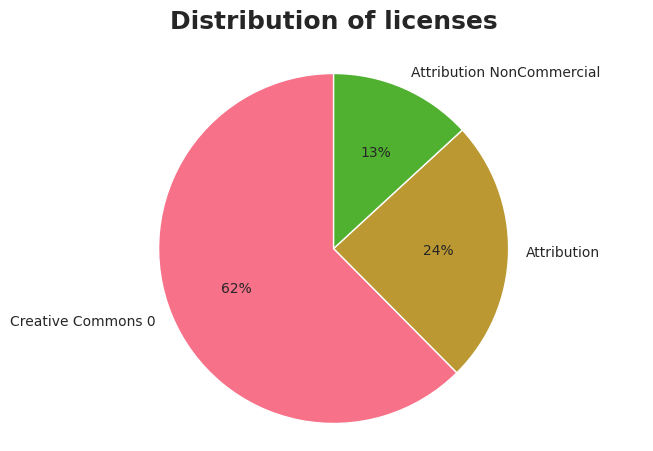

Another common discussion in relation to generative AI models is that of the restrictions that apply to training models with content released under Creative Commons (CC) licences. This is a complicated matter, and so far there are no clear and unambiguous answers to many of the questions that might arise. Nevertheless, we’ll try to answer the general question “Can my sounds be used to train AI models?” for the different licences with which sounds can be published in Freesound:

- Creative Commons 0 (CC0): this licence basically states that the sound is released to the public domain without copyright restrictions. Therefore, sounds under CC0 can have no copyright-related usage restrictions for training and distributing both predictive and generative AI models (note that we use the term predictive here to refer to AI models that do not generate any kind of content).

- Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY): the “BY” clause of this licence specifies that, if a particular sound is used to create some other work (an adaptation or derivative work), attribution should be given to the author of that sound. The first question therefore would be: should an AI model be considered an adaptation/derivative work of the sounds used to train it? Even though there is so far no clear legal answer to this question, there is no doubt that an AI model is based on the data used to train it, and the data is what determines the characteristics of the model. Therefore, we recommend that AI models (predictive and generative) only use CC-BY sounds for training if, on distribution or publication, they provide attribution. This attribution should be given at least to all CC-BY sounds included in the training set, and should be accessible through a public URL containing the list of sounds. However, in the case of generative AI models, what happens with the sounds that are generated? So here comes the second question: should sounds generated by an AI model also be considered adaptation/derivative works of the sounds used to train the model? Answering this second question is even harder than answering the first one, and the answer could depend on the nature of the actual sounds being generated. It could be the case that a model generates sounds which only feature small transformations with respect to individual sounds of the training set, or sounds that reproduce entire chunks of training sounds. In that case, the generated sounds could be considered reproductions or adaptations/derivative works of the sounds in the training set. This is what happens when models have memorisation issues, and this is something that AI researchers try to avoid. However, the most common case is that a model generates sounds which don’t have clear individual references in the training set, and in that case these will not be considered adaptations/derivative works. If a generated sound was to be considered an adaptation/derivative work, then, wherever the generated sound was used, attribution should be given to the CC-BY sounds used to train the generative model. But if the sound was not considered an adaptation/derivative work, then no attribution would be required. We therefore think that, as a general rule, sounds generated by AI do not need to provide attribution to the individual sounds of the training set of the model. Nevertheless, we believe that a best-practice for AI models trained with CC-BY sounds would be to recommend their users to provide attribution to the models themselves in the works they create, that is to say, to be transparent about the fact that the a work includes AI-generated sounds, and which models were used to generate them. For example, model creators could recommend their users to use a wording like this: this work uses sounds which were generated using the AI-model X.

- Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial (CC-BY-NC): sounds released under the CC-BY-NC licence provide the same copyright restrictions as sounds with CC-BY, with the addition that those sounds should not be used for commercial purposes. Therefore, what we have written for CC-BY applies to CC-BY-NC as long as the AI models are not used in a commercial setting or for a commercial purpose (as defined by the NC term of the Creative Commons licence). In a commercial setting, CC-BY-NC sounds should not be used for training AI models (both predictive or generative), and AI models trained with CC-BY-NC can not be distributed.

- Sampling Plus (CC-Sampling+): even though CC-Sampling+ is a legacy licence and its use is discouraged by Creative Commons since 2012, it was used at the very beginning of Freesound and there are ~11k sounds that bear it. For what AI is concerned, we interpret the CC-Sampling+ licence in a very similar way to CC-BY, as it does require attribution similar to the “BY” clause. Even though the sharing of the sounds as-is in a commercial setting is not permitted in CC-Sampling+, this is not the case when distributing AI models, and therefore no commercial limitations would apply. Therefore, our recommendation is that AI models can use CC-Sampling+ sounds as long as attribution is provided in a similar way to CC-BY sounds.

One important thing to mention however is that all the above restrictions are only concerning copyright. There are no copyright restrictions on non-copyrightable works, and there are exceptions in the copyright law that could allow the use of copyrighted works without permission of the copyright holders. In addition, there might be other considerations beyond copyright (e.g. database rights, privacy, security) that might affect decisions of whether it should be allowed or not to use some specific works for training AI models. Therefore, CC licences are not the only relevant thing to take into account to answer the question “Can my sounds be used to train AI models?”. For those who want to know more, you can read this blog post published by Creative Commons, and follow extra links there.

In summary, if you are a Freesound user and you are concerned about your sounds being used for AI, the most restrictive choice you have is to use CC-BY-NC to avoid having your sounds used for training commercial models. Alternatively, a middle option is to use CC-BY which will allow commercial uses but will, at the very least, help enforce transparency of AI models by promoting a disclosure of the training set (or part of it).

How can AI benefit Freesound?

So far we only talked about AI threats and restrictions for training and distributing AI generative models, but there is indeed a lot of good stuff that AI has to bring, so let’s now look into that.

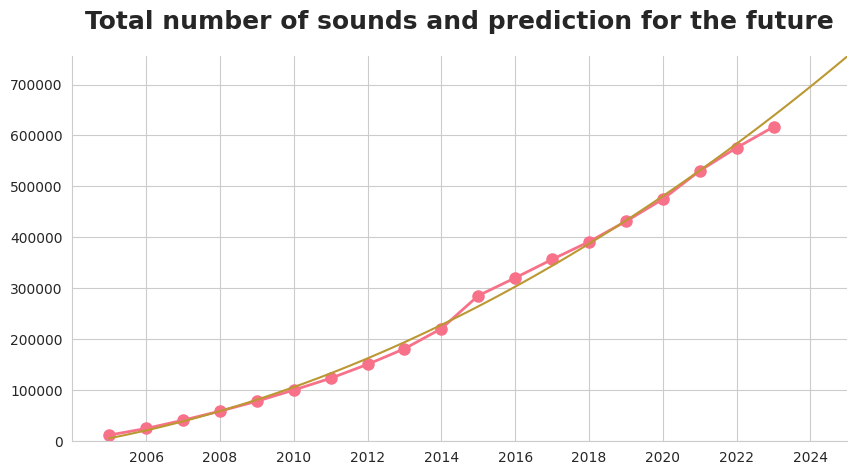

First of all, let us remind you again that Freesound is a project that was born in a research group of a public university, and we, at the research group, have been working on AI for many years. Freesound is indeed a very valuable resource for AI research all over the world, an indication of that being the over 850 research papers citing Freesound. This has a tremendous impact on all audio-related research fields. AI models (or machine learning models as we used to call them before the AI boom) trained on data from Freesound are being used for many research tasks such as automatic sound identification and localization, speech recognition and acoustic scene classification (to name a few). In fact, AI models are already powering some Freesound features like sound similarity and tag recommendation, and will power other features with which we have experimented but which have not been deployed. Furthermore, the Freesound community is often invited to participate in research experiments through which feedback is collected that informs research and that eventually allows the development of new features that are deployed in Freesound and benefit the community. The Freesound community and predictive AI research are already a good example of a synergetic ecosystem.

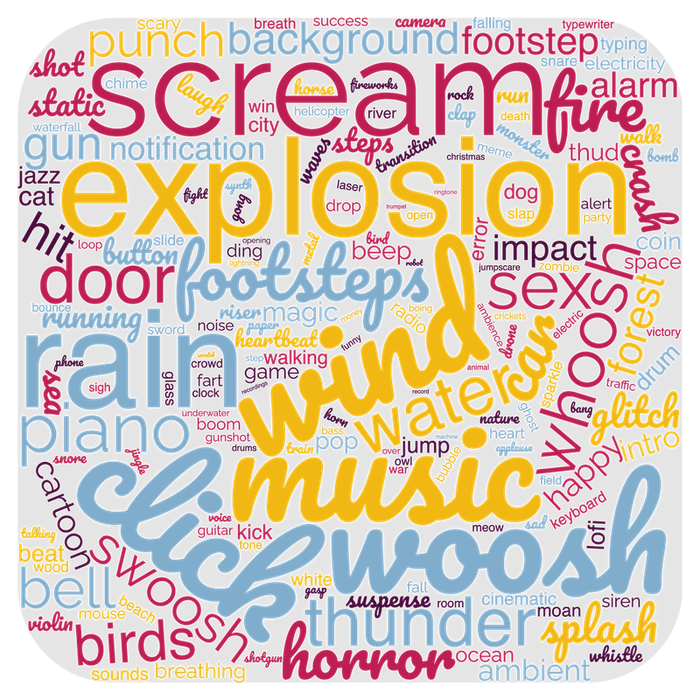

However, it could be argued that the challenge comes with generative AI. While the threats with generative AI are real and we have to assume that some things will change in the future, generative AI also has a great potential to benefit the community. Using AI tools that generate sounds, we can explore new sonic realms which were not available before, and new forms of art, aesthetics and sound sharing can emerge. Generative AI could also be used for sound transformation instead of from-scratch generation, and this could be a very useful sound design tool for the community which could potentially be integrated into Freesound. With such a tool we might be able to transform sounds in a way that would allow us to make footsteps “heavier”, or an explosion “softer”, or make a “car sound like a dolphin”, or separate mixed events in the same sound. And these are just some examples.

The overall question is how to use and integrate AI technology in a way that benefits the Freesound community, and this is what we are starting to address with this blog post. At the Music Technology Group, we conduct cutting-edge AI research while considering its social, economic, legal, ethical, cultural, and artistic implications. Research is being carried out, not only by us but also by many other research institutions, which provides new ways to address the threats raised by AI, contributing to a fair and responsible AI. And, again, Freesound is a very important resource for such research. In a similar way in which Freesound became a great example of a sound-sharing ecosystem based on Creative Commons licences, we have the opportunity now to become an inspiring example of how AI can be used to empower a community and to articulate positive experiences for sound practitioners alike.

Let us finish by saying that the contents of this blog post mainly represent the opinion of the Freesound team of the Music Technology Group, but have also been shared and discussed with the team of Freesound moderators who have provided great insights. Also, we are very thankful for the comments from Malcolm Bain at Across Legal, Barcelona.

Thanks for reading until the end, and please let us know what you think in the comments section forum thread that we created for this topic 🙂

…the Freesound Team